How can governments pursue meaningful industrial policy in the 21st century? How can they incentivise new markets to lead the twin transition? How can they create good jobs for future disadvantaged workers? Most importantly, can the current setup of government achieve these essential transformations? In this white paper, we propose a way to think about and implement missions that can unleash them beyond mere policy tools, launching a new type of governance for the 21st century.

How can governments pursue meaningful industrial policy in the 21st century? How can they incentivise new markets to lead the twin transition? How can they create good jobs for future disadvantaged workers?

Most importantly, can the current setup of government achieve these essential transformations?

In this white paper, we propose a way to think about and implement missions that can unleash them beyond mere policy tools, launching a new type of governance for the 21st century.

The rise of mission-oriented innovation policy (MOIP) has given policymakers a practical approach to enabling and accelerating societal, economic, and technological transformations. The main premise behind its ever-growing dissemination across global policy networks is straightforward: in the face of the challenges posed by the 21st century, traditional innovation policy is broken.

Indeed, between 2010 and 2020, governments did not invest in clean energy as much as they should have; there was slow growth in markets for education, care, and other social services; and even antivirals were underfunded, leading to a slower response to the pandemic.

What is mission-oriented innovation policy?

MOIP describes a package of policies designed to mobilise science, technology and innovation in order to solve grand societal challenges. After Mariana Mazzucato’s seminal work The Entrepreneurial State, missions quickly entered the mainstream of policy – notably, at last, through the European Commission’s EU Missions in Horizon Europe.

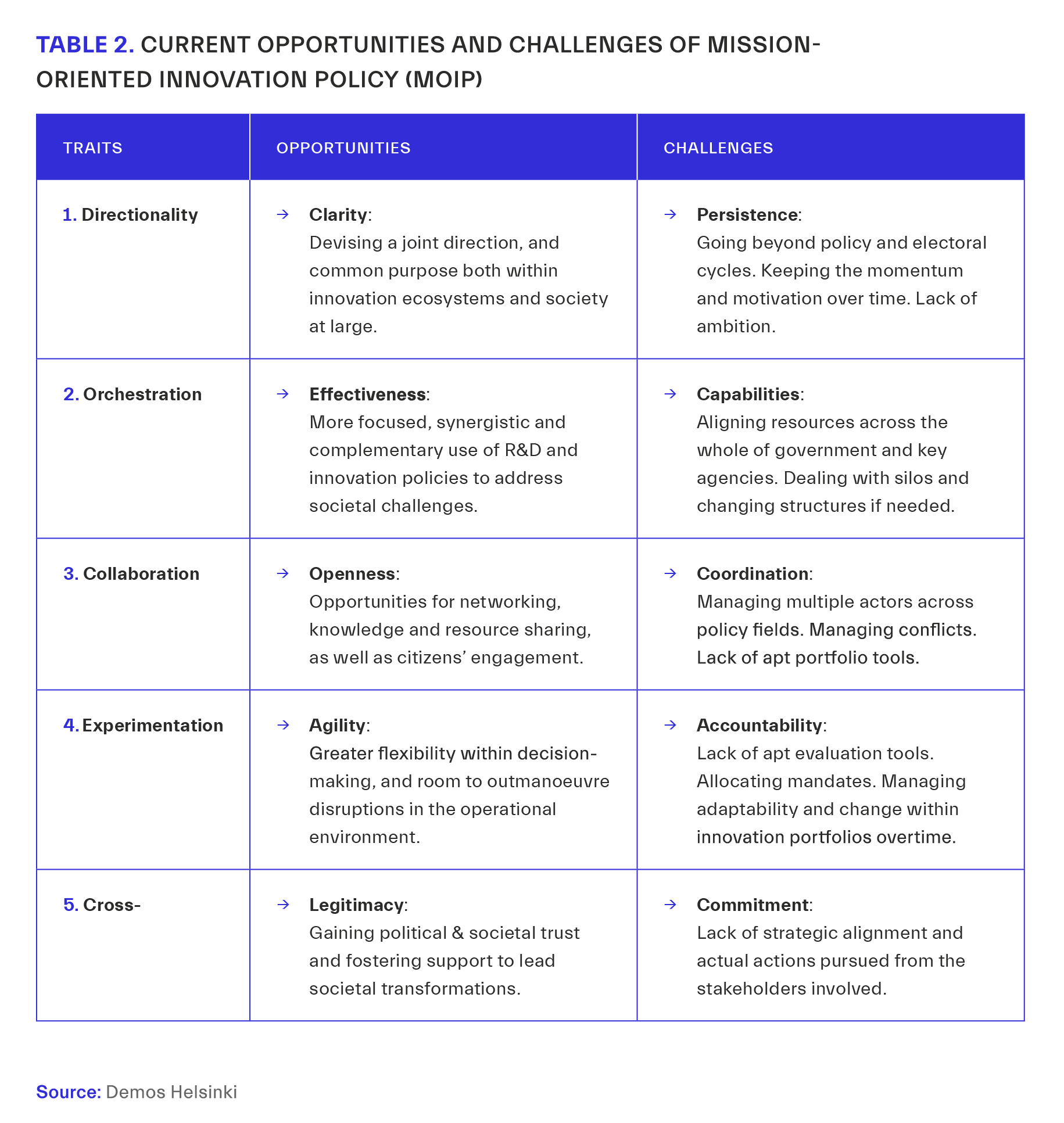

The definition of MOIP remains plural and evolving. In this paper, we synthesise its main characteristics from the existing literature and summarise them as follows:

- Directionality: MOIP targets a set of objectives that the actors involved in a mission can commit to pursuing through social and technological innovation.

- Orchestration: MOIP relies on pivotal organisations with capabilities and tools to steer and engage with multiple resources and stakeholders.

- Collaboration: MOIP enables and accelerates the systematic integration and coordination of multiple streams of action beyond existing structures and processes.

- Experimentation: MOIP enables and accelerates systematic testing, revision, and learning from different solutions to tackle a given challenge.

- Cross-: MOIP commits to leveraging inputs, efforts, outcomes, and learnings from actors that have diverse institutional, sectoral or disciplinary backgrounds.

Current challenges with the mission-oriented approach

Based on a 2022 OECD survey:

- Only 1 in 4 practitioners of MOIP had a clearly defined target

- Only 15% stated to have a dedicated structure of governance for MOIP

- Only 1 in 10 had a clear plan and process for monitoring and evaluation

While MOIP shows a direction for how governments can reignite innovation policy, it does not solve alone the key challenges that governments are facing in steering societal transformation. For example, electoral cycles, governmental silos, low capabilities and the need for broad collaboration pose radical challenges to how the theoretical potential of MOIP is translated into practice.

These challenges urged us to dissect what could unshackle policymakers from the past and look for what could empower them to drive forward meaningful and transformative innovation policies.

A new path forward: Thinking missions as governance

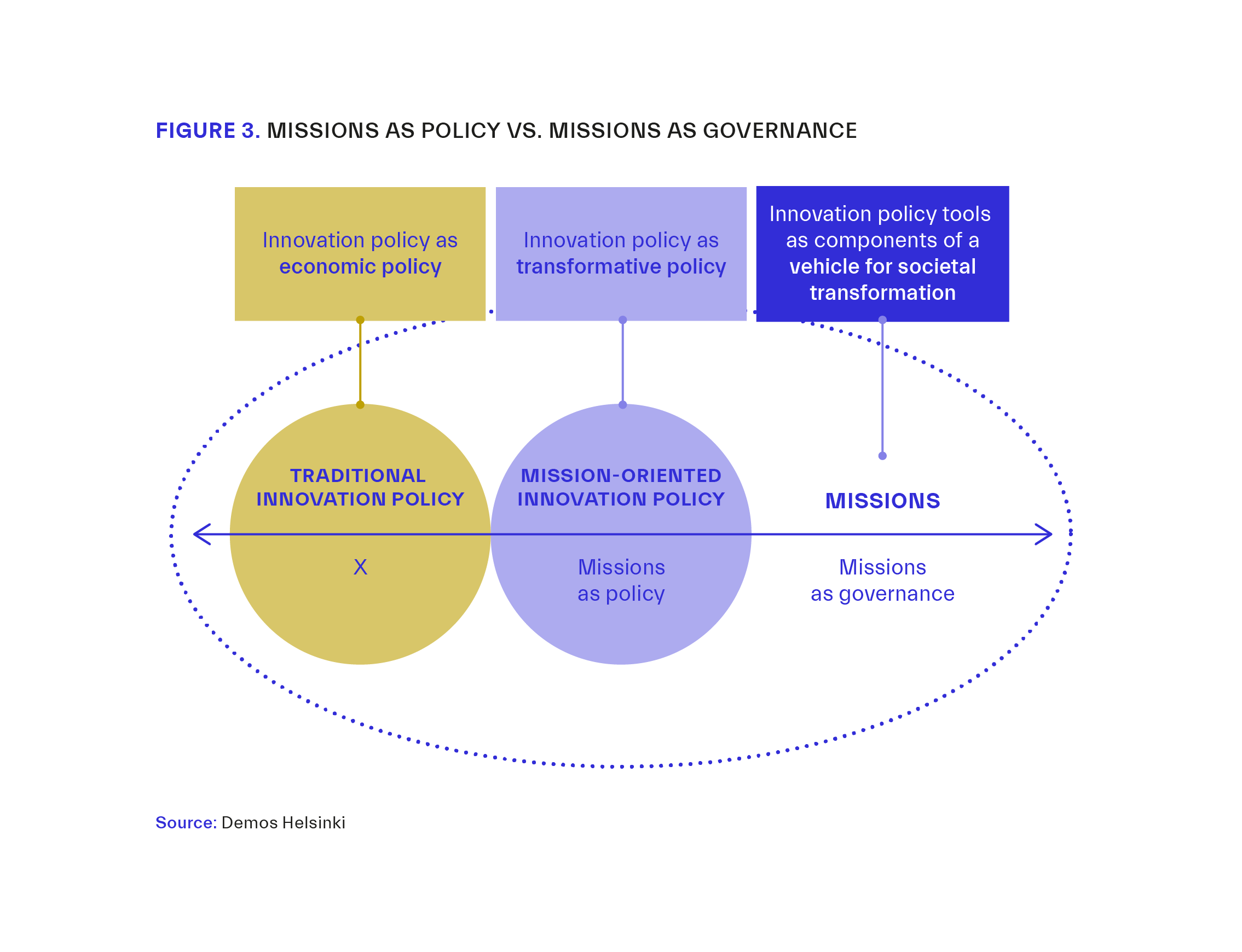

MOIP’s true potential relies not simply on the need to reboot innovation policy, but on the paramount opportunity it provides to challenge established ways of thinking, doing, and implementing governance. To make the most of MOIP, governments and policymakers need to stop talking about missions as policy and start exploring missions as vehicles for governing societal transformations. Seeing missions as governance helps us understand that:

- Their potential cannot be achieved within existing structures of government.

- There is no necessary dichotomy between traditional innovation policy and MOIP.

To build transformative mission-oriented innovation, governments should rethink how their branches operate with each other and with external actors: how governance is planned and implemented.

To do so, we recommend that forward-looking, visionary governments rethink:

1. Designing missions

Nurture a broad consensus and agenda on grand societal challenges: who should have a say in defining them (i.e., stakeholders, citizens, etc.)? And how should they be engaged?

Recommendations

- Define, specify and prioritise clear-cut societal objectives

- Ensure collective ownership by including public, private and civic stakeholders

- Create powerful and inclusive narratives that provide the right incentives

2. Organising missions

Develop a strategic overview of how your government can meet such an agenda: who should lead transformative change? How should public actors coordinate for making it happen?

Recommendations

- Set clear responsibilities, accountabilities and ownership

- Create mission-oriented teams and processes

- Ensure coordination among public actors

3. Governing missions

Ensure that your government has the resources and instruments to get the ball rolling. What capabilities would be needed to help civil servants accomplish transformative objectives? And what policy tools – old and new – should be leveraged to ensure their ability to do so?

Recommendations

- Build collaborative and experimental capacities in the civil service

- Provide front-line managers with decision-making autonomy

- Develop ways to facilitate knowledge sharing

Conclusion

The transformative potential of missions cannot be liberated if accommodated within the boundaries of existing structures, processes, and mechanisms of government.

This white paper serves not only as a preliminary basis for nurturing an alignment about the scale and potential of this effort, but also as a broader call to action for any other stakeholder that is curious and committed to further with us our collective exploration of this vehicle. The time to get serious about societal transformation is now. It is up to you and us, then, to turn on the engine and put this vehicle into motion.

How can your government start to build a missions framework to address long-term societal challenges? Please get in touch with:

Iacopo Gronchi

Transformative Governance Expert

iacopo.gronchi@demoshelsinki.fi

The big “how”: New ways to govern industrial policy

Post

July 13, 2023

An operative model for implementing missions

Publication

May 8, 2023

FIMO – A framework for a Finnish model of mission-oriented innovation policy

Project

September 19, 2022

The changing role of the state in the economy

Publication

April 26, 2023

NetZeroCities — Helping European cities reach net zero by 2030

Project

March 3, 2022