Cities are no longer just drivers of climate action but must now transform themselves into leaders of collective action. As we shift from gradual low-carbonisation to rapid decarbonisation, cities must rethink their role, governance, and tools to address the climate crisis and foster coordinated efforts for sustainable change.

Cities are accustomed to thinking they drive climate action. Now, this thinking has turned into an obstacle. In line with a world shifting from gradual low-carbonisation to fast decarbonisation, abrupt changes in technology, globalisation, the economy, and climate sentiment, cities must dismantle their old tools and transform. From now on, if cities want to be part of the solution, they cannot simply be enablers of change: they must be the testing grounds for new forms of collective action.

A whole other story

For a long time, cities got to have the cake and eat it: solve the climate crisis but not change how they operate. City leaders thought that cities not only hold the keys to decarbonisation but that the necessary investments, innovation and recognition would all occur within the cities’ grounds. Climate change would keep Mayors on the global table. Meanwhile, cities’ livability and their economy would keep growing (consequently keeping Mayors in office).

This thinking became mainstream seven years ago in Paris — seemingly also supported by evidence. The IPCC’s Fourth Assessment Report, published in 2007, already mentioned cities as essential sites for climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies. But it was COP21, with its binding targets, that solidified cities’ central role in climate action, making climate a strategic issue for cities. Since Paris, we learned this argument by heart: over 50% of the world’s population lives in cities, and cities account for about 70% of emissions. More importantly, we learned to say that because cities are near the people, they bear innovations and develop sustainable lifestyles, galvanising unforeseen global markets to create smart and sustainable urban solutions.

The assumption that cities lead climate action has since then become entrenched. Never before has the IPCC highlighted the role of cities in climate change mitigation and adaptation to the extent of its two most recent reports. Supporting this narrative, cities have also found it easier to set ambitious targets. Around 11,500 local governments have committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions and adapting to climate change through the Global Covenant of Mayors. The 1,000+ cities and local governments signing onto the Race to Zero represent 722 million people.

This year, the belief in cities’ central role at COP27 was still strong, but the discussion was far more nuanced. London’s Lord Mayor Sadiq Khan‘s statement illustrates the change in nuance. Instead of centring cities, he calls for other levels of government to join. “Cities are using every lever we have to take meaningful climate action now — but we cannot avert a catastrophe of this magnitude alone.” It may be a small change, but it means a lot. If previous years have been about cities’ central role, this year is about bringing accountability at all levels, from global to personal. Where previously mayors have bolstered their cities’ capacities in delivering climate action, they are now asking others to join so they can do their part.

Loss and damage fund aside, the #COP27 agreement is a missed opportunity for national governments to meet the scale of the challenge we face.

Cities are using every lever we have to take meaningful climate action now – but we cannot avert a catastrophe of this magnitude alone.

— Sadiq Khan (@SadiqKhan) November 20, 2022

I believe this was just the beginning. Cities sense that the established argument does not hold, and they are now seeking a new role.

To understand what cities’ new role in climate action could be, let’s have a look at what has changed since Paris.

1 From low to zero carbon

Starting with the obvious, decarbonisation has been slower than expected, more rapidly enforcing zero carbon as an absolute necessity. Climate change gave way to climate crisis and climate emergency. The steepness of the carbon-neutrality curve keeps growing. As a result, mitigation through an incremental change in production and consumption is no longer an option. Now, carbon needs to be stored, cities rewilded, and massive areas of land forested.

Going from low carbon to zero carbon is not a quantitative change; it’s qualitative. Indeed, most of the largest cities in the world are reducing per capita emissions far faster than national governments. But this is not the point anymore. Decarbonisation metrics are shifting from carbon footprints and life cycle assessments to carbon budgets, sinks and spikes. At the current construction growth trajectories — building one New York City per month for the next forty years —, having low or even zero-carbon construction materials is not enough. The zero-carbon infrastructure of batteries, chargers, solar/wind farms and rails alone fills a big part of the existing carbon budget, not leaving much room for new houses, offices, or shopping centres. With such volumes, cities will blow our carbon budget in a matter of years despite their better performance relative to nations or new construction projects with low emissions over a lifecycle.

With construction being off-limits, zero carbon for cities means finding new ways to attract investment, drive the economy, and steer climate action. Zero carbon, beyond questioning cities’ economic model, also challenges cities’ political power. When building more can no longer be the starting point of urban growth, power over land use becomes a less helpful steering mechanism.

2 Other forces undermining cities’ role in climate action

It’s not only the shift from low to zero carbon that is undermining cities’ role in leading climate action. In the last few years, many of the forces that were supposed to put cities in the driver’s seat have taken new turns.

– The focus of economic policy has shifted from introducing innovative consumer services and products into global markets to infrastructure, industrial, fiscal and monetary policies at national and multilateral levels. Consequently, the anticipated massive investments for both recovery and climate transition may end up going to infrastructure megaprojects, such as EV-charging, electrification, massive renewable energy “farms”, smart grids, and transportation infrastructure. This is very far from the story that “cities are innovation ecosystems and living labs”.

– Digital services that were thought to be a considerable part of cities’ contribution to climate action have not delivered significant climate impacts. The smart and green cities have not fully materialised. In many cases, services have even rolled back as venture capital moved to opportunities with quicker payout. Instead of holistic smart cities, where emissions are curbed with efficiencies reached through smart information, coordination and sharing services, VC money has gone to automating financial and professional services, electrification and security. Looking at climate investments alone, we see a focus on energy and transportation. Yet, these investments do not enable the transformation of smart mobility services but the electrification of existing networks. Despite exciting developments in urban energy, micromobility, and home delivery, there are simply not enough scalable decarbonising digital services. Cities have been unable to steer digital technology and business development towards their complex goals.

– The anticipated global markets for urban-level solutions have not emerged, despite city networks and cities’ attempts at transferring best practices and technologies from city to city. Globalisation, which once benefited cities immensely, is taking a new turn — particularly in technology. Competition in high tech between China and the US, and now in the EU, has unleashed a regionalist force that seeks to cut global interdependencies rather than foster them. Needless to say that the Russian attack on Ukraine has given manyfold speed to this regionalising force, currently most visibly through energy policy. Decarbonisation may also be deglobalisation, as renewable energy cuts the dependency on international (fossil fuel) trade. All these regionalising tendencies put uncertainty on (city-led) globalisation and increase the weight of national and supranational governments.

– Most notably for cities, the tonality of climate politics and attitudes has shifted dramatically in the last seven years. From hope and sustainable lifestyles, we now hear heavier notes reflecting values, protests and anxiety, especially among the young. The 2022 energy crisis, which has exacerbated energy poverty in cities and has brought energy security to the fore, is already creating a morbid tone for climate politics. Civil society reflects this change: before, campaigners confronted deniers with science and activists called for dense livability, sustainable lifestyles and climate entrepreneurship. Now, activism is about breaking new political ground through urban protests designed to obstruct public order and values. City streets are a medium for collective action, protest, and global politics.

A new era for cities: instigating and governing collective action

Let’s re-examine how cities can significantly solve the climate crisis. To me, the mantra of cities having 50% of people, accounting for 70% of emissions, and being the biggest addressable market (ever!) for climate-smart solutions rings only half true today. It is true that people live primarily in cities and that cities emit a lot of carbon, but the paradigmatic shifts outlined above question the plausibility of cities creating global markets for urban climate solutions. At least, they challenge the established role of cities in climate action.

In hindsight, one could perhaps argue that cities could have led climate action, but city leaders took a far too passive role — the role of an enabler. Cities have focused on enabling, facilitating, providing experiment platforms, orchestrating ecosystems, joining international networks, spreading best practices, attracting, procuring, incorporating, deregulating, competing, and amplificating local solutions to global markets as a way to lead climate action. This lens makes it easy to see why cities thought they could lead globally without leading locally.

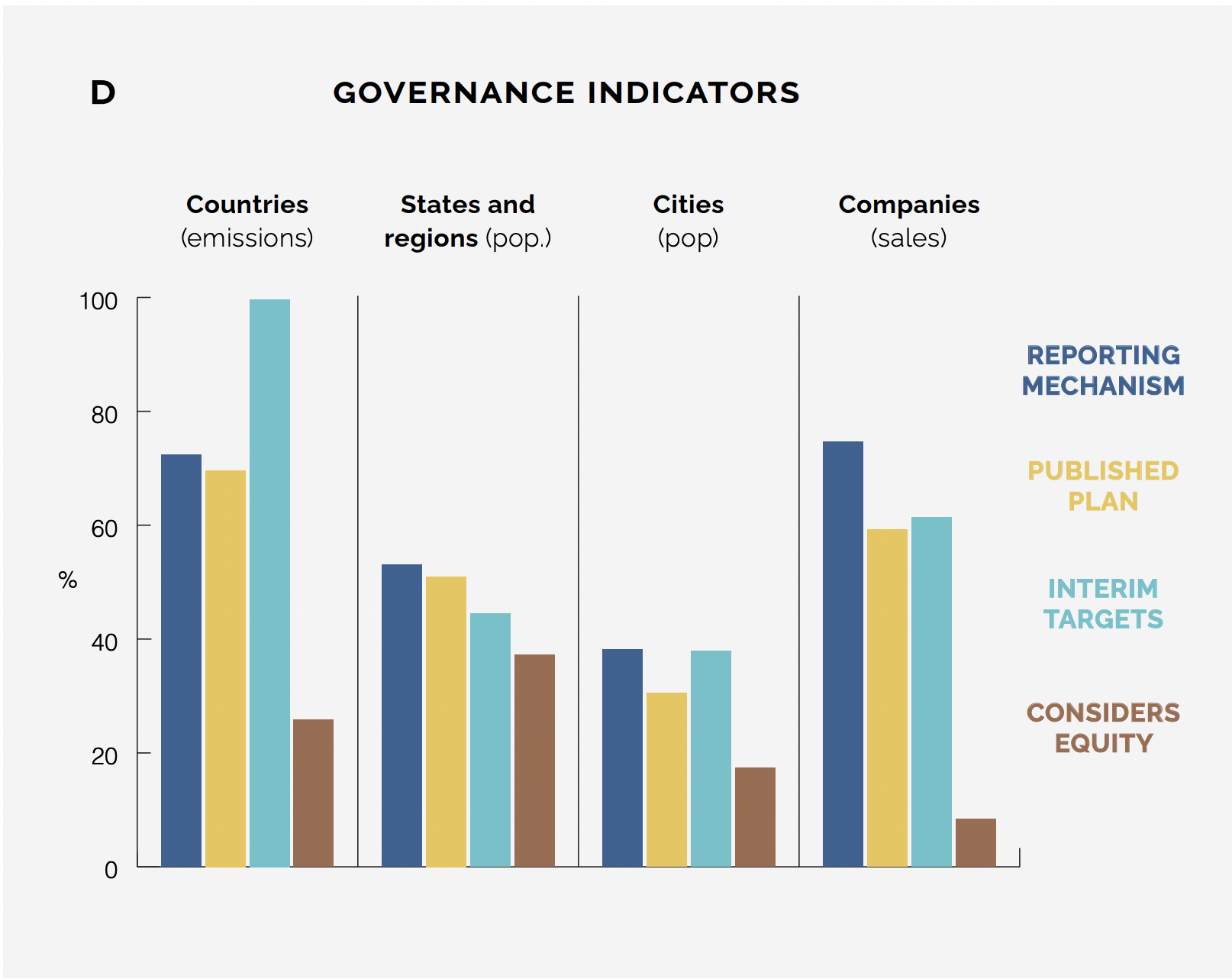

Figure 1. Cities are lagging behind countries, states, and companies in almost all governance indicators

Source: Energy & Climate Intelligence Unit (2021). Taking Stock: A Global Assessment of Net-Zero Targets.

Could there be another role for cities in climate action? What if we took a step back and saw what is missing from climate action and how cities may contribute to it?

The climate crisis is not a failure of investments or policies but a failure of collective action. Seen through this lens, the climate crisis is also not a question of individual or institutional transformation and responsibility; it’s a question of having both support each other. If we accept this hypothesis, the task at hand is not innovation in the form of products and business models but innovation in the form of collective action, institutions, and, in a word, governance. Cities must “capture” the power of worry related to the climate crisis and turn it into legitimate, trustworthy, and proactive institutions.

Reflecting on the past seven years and after the end of COP27, the need to re-evaluate what cities can do to drive climate action is paramount. Demos Helsinki has long argued for cities as vehicles of collective action. In 2022, cities are still uniquely positioned to build meaningful relationships between government and people. Now, they need to phase out the narrative by which transformation naturally “happens” in their surface area. Cities’ aim should not be to provide the physical space for organic disruption but to instigate and govern collective action towards a fair, sustainable and joyful next era.

To all Mayors and local governments: with your buy-in, this can be only the beginning.

Up next: Chapter 2: Co-building the next city narrative

Read more:

- The wellbeing of the Metropolis, a Demos Helsinki publication so far back that we had a different logo (2014).

- City 2.0 — Towards a social Sillicon Valley, a Demos Helsinki manifesto from 2015, which rings true to this day (in our humble opinion).

- People first: A vision for the global urban age, a 2020 Demos Helsinki publication exploring the role of cities in techology development.

- The climate crisis is a governance crisis, an article we wrote for COP26.

Feature Image: iStock/amoklv

People First: A Vision for the Global Urban Age

Publication

June 8, 2020

The climate crisis is a governance crisis

Post

November 10, 2021

Climate governance and cities: leading the next decade

Post

February 14, 2023

Sustainability Governance in the City of Tallinn

Project

June 21, 2023

NetZeroCities — Helping European cities reach net zero by 2030

Project

March 3, 2022

Solving clusters of challenges in sustainable city transition

Project

March 10, 2023

Transforming cities

Theme

November 11, 2024