The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted how health crises are interconnected with political, social, and economic factors. Syndemic theory explains how overlapping health and social issues, like poverty and violence, worsen each other. Applying this concept to future health governance could improve decision-making by considering broader societal impacts and fostering resilience.

If the era of COVID-19 taught us anything, it’s the importance of viewing health and socioeconomic factors as mutually reinforcing. The past years have highlighted how health crises are not only biomedical phenomena but rather intrinsically encompass political, social, cultural and economic dimensions. Future health governance could serve its purpose with more zeal and efficiency if it started to account for “syndemics”.

By Emilia Laine

In this article:

- What are syndemics?

- Why should we care about them?

- Are syndemics only about health?

- What does this mean for the future of health governance?

- What can we do to build resilient health governance?

What are syndemics?

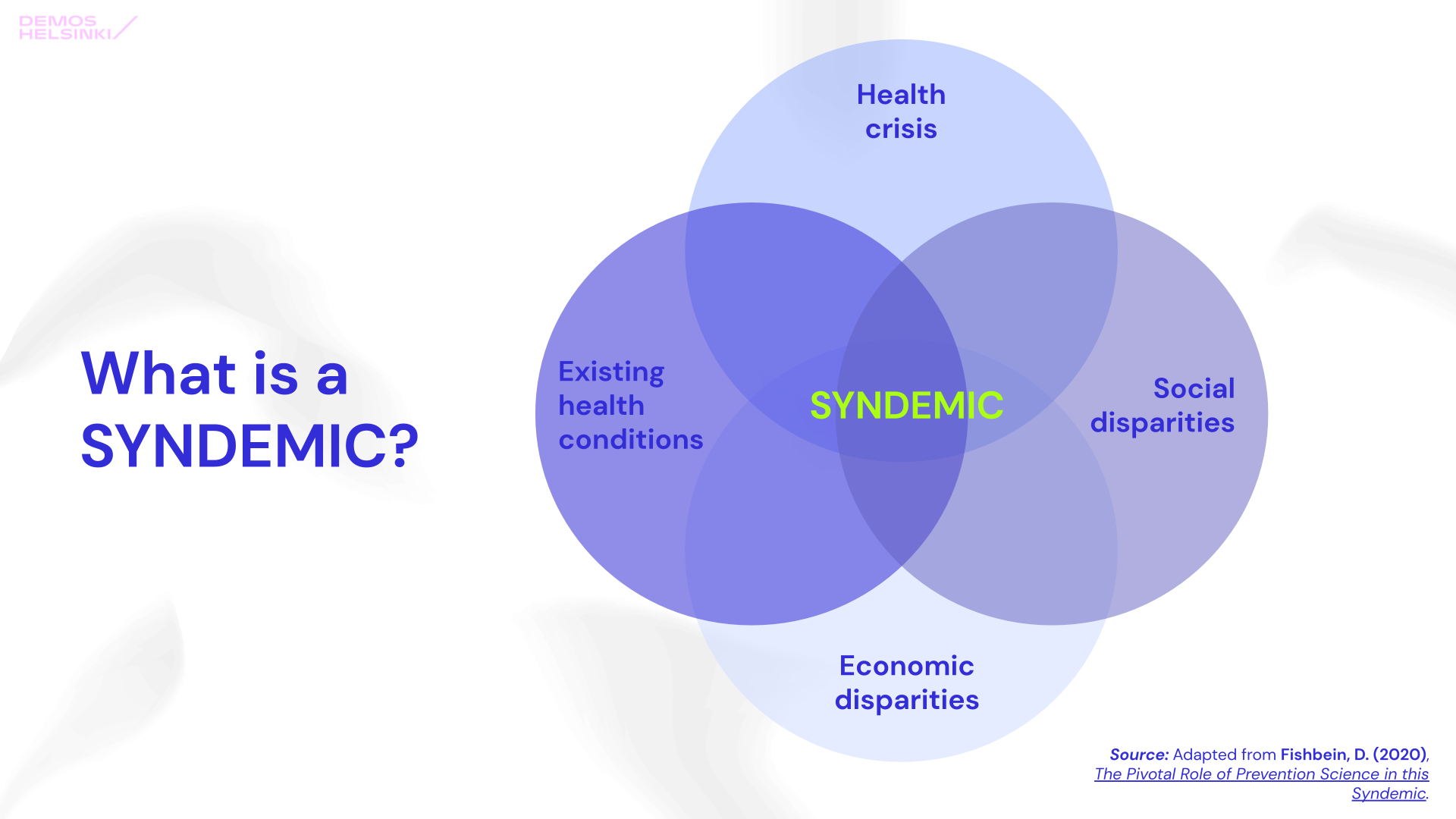

The term syndemic describes a situation in which two or more health and social factors are clustered together, and their interaction further worsens the community’s overall health. Introducing this term in our thinking allows us to view these factors as interlinked and mutually reinforcing — instead of parallel but separate epidemics. Consequently, syndemic theory explains why we observe an accumulation of health and social problems in specific populations or groups.

Why should we care about syndemics?

By studying the concurrent epidemics of addictions, poverty, violence and HIV/AIDS, Merrill Singer (1996) noted that these health and social issues were interrelated and they influenced each other. According to Singer, a syndemic occurs when a) two or more diseases or health conditions are clustered together, b) these conditions worsen each other and increase the overall health burden, and c) there are social conditions, such as social isolation and poverty, which create conditions for clustering and synergistic interaction.

Syndemic theory invites us to ask why a specific clustering occurs in a particular population rather than viewing health from the perspective of an individual. Consequently, it emphasises that health and social problems accumulate among those already in marginalised and impoverished positions. As a result, syndemics inherently reveal questions of power and privilege.

For instance, the VIDDA syndemic (Mendelhall 2012) describes the interconnections of violence, immigration/isolation, depression, diabetes and abuse among Mexican women living in the United States. When combining structural stressors such as systemic violence, poverty and immigration with adverse relationship factors such as interpersonal abuse, Mexican immigrant women are more likely to develop diabetes and depression than the overall population.

Are syndemics only about health?

In short, they shouldn’t be. Syndemic theory has evolved to account for cumulative health risks and socioeconomic conditions that could make specific populations more vulnerable. For instance, Sangaramoorthy & Benton (2021) call for adopting an intersectional lens to increase our understanding of what makes particular populations vulnerable – struggling to make ends meet, caring for an ill person at home, or belonging to a marginalised group. In other words, by being more aware of these underlying specific conditions, we can diminish the syndemic effects on those already vulnerable.

Source: Adapted from Fishbein, D. (2020), The Pivotal Role of Prevention Science in this Syndemic.

The example of COVID-19

No other example has revealed the interconnection of health and social problems more broadly than the COVID-19 pandemic. By thinking of COVID-19 as a syndemic, we can rethink our approach to the current and future health crises. In our real-world context, instead of a variety of parallel health problems creating a syndemic, the contagious disease COVID-19 is added to the pre-existing constellation of social and health issues.

Introducing syndemics to the public discussion could help us understand the implications of health crises on different populations and, as a result, foster empathy. In research, using syndemic theory to guide collecting, combining and analysing data has been instrumental in showcasing the inequity of social conditions. Not everyone experienced the pandemic with an equal sense of danger. As a result, the health risk became an additional risk for people already in a precarious social position.

What does this mean for the future of health governance?

1. Race, gender and other social factors matter as explanatory variables

Not having the ability or means to work from home implies a higher risk of getting infected. At the beginning of the pandemic, black men of African background living in the UK had COVID-19 death rates 2.5 times higher than white men. According to UK National Statistics, the difference did not stem from pre-existing health conditions but socioeconomic and demographic factors or exposure at work. Thus, being outside the home during a quarantine should not be used politically as a signal of disorderly, antisocial behaviour since it may also simply signal the necessity of earning a living.

2. Social and economic policies are correlated to health, and vice versa

The past two years have also highlighted that a narrow medical response and its traditional indicators do not provide enough information about the societal consequences of an infectious disease. Instead of limiting the governmental response to the imminent health implications, the syndemic approach extends the invitation to other policy areas such as education, employment, housing, food, and the environment.

The policies aiming to tackle the spread of COVID-19 have also created conditions for the accumulation of other socioeconomic problems. For instance, while maintaining the remote work policy at universities and workplaces for two consecutive years might have been an effective measure to prevent the spreading of the virus, it has spurred a mental health epidemic that is likely to unfold during the coming years. Additionally, the pandemic restrictions have led to temporary unemployment in some low-paying occupations, such as the service industry, where employees might have fewer savings for these unexpected events such as lay-offs.

3. Looking at broader positive effects of a crisis can create valuable feedback loops across policy areas

Although health crises might escalate other societal problems, they can have surprising positive consequences. For instance, the slight decrease in CO2 emissions at the beginning of the pandemic led to improved air quality in many regions. In Europe, the enhanced air quality decreased air pollution-related deaths and proved that it is possible to cut down greenhouse gas emissions rapidly. The pandemic also enabled an unforeseeably fast socio-technical transition in working conditions as organisations had to transition into remote work overnight. At least in the Finnish context, some of the implications were surprisingly positive, as the novel home-centric lifestyle encouraged people to spend more time sleeping, baking and walking outdoors.

What can we do now to build resilient health governance?

Firstly, to improve societal wellbeing after the pandemic, it is essential to identify and locate the underlying social and health-related problems that the pandemic and its related policies have been reinforcing. However, shortcomings in the national-level data collection efforts can make the application of syndemic theory challenging, as has been the case in Finland.

Secondly, we need to find avenues for collaboration between different social and health sciences. Adopting a syndemic approach poses multiple challenges to decision-making as the extra dimensions are bound to have incommensurable governance demands. As it entails combining knowledge from various stakeholders representing a versatile set of ideologies, it leads to the question of how political decision-makers value different sources of knowledge.

Lastly, responding to future health crises will require increased institutional resilience in health governance. This means less siloed governance with increased communication and coordination between different actors. While enhancing cooperation between various public institutions improves the resilience of the public crisis management infrastructure, it is likely to decrease efficiency — which policymakers often prioritise when evaluating the success of governance measures.

When analysing health crises such as COVID-19, the syndemic is an illustrative concept for policymakers as it helps to describe interlinkages between different health and societal dimensions. It can also encourage public servants to explore new tools, skills and structures required to locate these interlinkages. Therefore tuning into the syndemic nature of crises might initiate a learning process, which at its best, can lead to a more profound systemic change – both within governments and in societies at large.

Curious to see what syndemic governance would look like? Read more about WELGO, a research project that aims to safeguard welfare during health crises.

Feature Image: Mel Poole / Unsplash

WELGO — Safeguarding welfare in times of pandemics

Project

January 25, 2022