Digitalisation is no longer about computers; people and physical things are becoming hyperconnected with cheap, abundant sensors resulting in the merging of digital and physical realities. To meet these challenges, Nordic societies look for new ways to prosper in the era of hyperconnectivity while upholding the traditional Nordic values of…

Digitalisation is no longer about computers; people and physical things are becoming hyperconnected with cheap, abundant sensors resulting in the merging of digital and physical realities. To meet these challenges, Nordic societies look for new ways to prosper in the era of hyperconnectivity while upholding the traditional Nordic values of trust, equality and human-centrism.

A crucial question is how Nordic companies and startups can compete with these values on the global markets. Demos Helsinki wanted to uncover what is required for a successful Nordic hyperconnected business ecosystem to emerge. Assigned by Demos Helsinki, Aleksi Aaltonen, Assistant Professor at the Warwick Business School, browsed through over 2,000 issues from 60 top-tier management journals to find the answer. You can access the working paper, the first condensed analysis from this massive task, through this link.

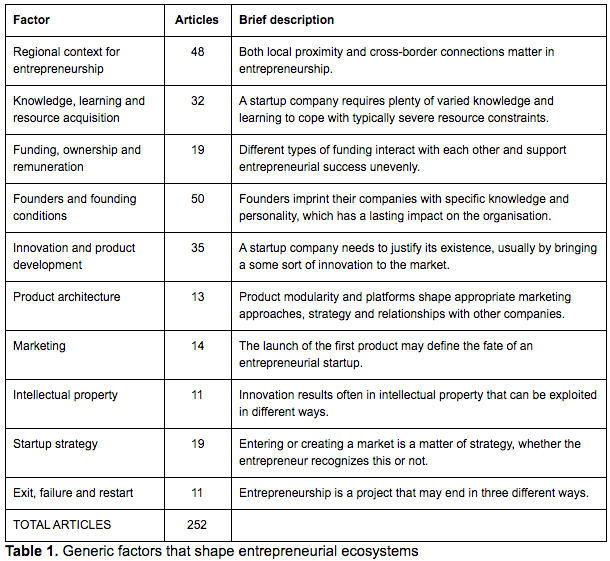

The working paper identifies the 10 most important topics from the literature(see table) and guides the reader to the key insights.

These are the seven most important findings from the research articles:

1. Not every great technology comes from Silicon Valley, but no startup can afford to ignore the US West Coast actors in hyperconnected high-technology business.

2. Entrepreneurship grows in local ecosystems, but most high-technology startups have to compete globally for customers and financing.

3. Regions can catalyse entrepreneurship by indirect interventions – throwing public money at startups does not necessarily generate successful ecosystems.

4. Key actors in entrepreneurial ecosystems are, in addition to entrepreneurs, investors, large companies, public authorities and universities.

5. Early-stage investors have a regional focus – to tap global capital flows, regions need local investors.

6. Entrepreneurial overconfidence may lead to excess new firms and failure, but traditional Finnish underconfidence results in missed opportunities without learning.

7. Any entrepreneurial firm has to consider at least two strategic issues irrespective of the market they are planning to enter: timing and incumbent reactions.

The working paper offers extensive insights on all of the aforementioned topics. The reader is left with some concrete suggestions, ranging from a three-year ‘entrepreneurship leave’ for academics to reduce the opportunity costs of trying out entrepreneurship to supporting regional startup ecosystems by developing the capabilities of local industrial corporations to acquire startups. These are good ideas just waiting to be implemented: it is up to the reader to become a champion for this change.

I am confident that the review can help Nordic decision-makers, universities, research clusters and startup communities to create a winning hyperconnected business ecosystem.