In this blog post I’ll first discuss about the purpose of the economy and second, I’ll pinpoint the discussion to one specific solution to a problem of the current economic policy. This solution is called the Economy of Wellbeing. I hope that the insights for these two topics awoke interesting…

In this blog post I’ll first discuss about the purpose of the economy and second, I’ll pinpoint the discussion to one specific solution to a problem of the current economic policy. This solution is called the Economy of Wellbeing.

I hope that the insights for these two topics awoke interesting comments and inspiration. Everything I’m going to say comes from the Demos Helsinki publication that admittedly has a rather long title, “A Transition to Just and Green Societies in the EU Requires Fixing the Economic Policy: A suggestion for implementing Economy of Wellbeing”.

Nevertheless, even before going to the contents of the publication, I want to highlight an important economic fact: If there is a greater growth of capital in our economy, we have more wealth available for taxation and distribution. If there is a smaller growth of capital in our economy, we have less wealth available for taxation and distribution.

A typical political discussion is about how we should distribute our wealth. The question of how much wealth we have to distribute is determined by the growth of capital we are able to sustain in our economy. This growth of capital is based on a specific conceptualisation of social wealth, which we often take as a natural fact. It is, however, something that we people have decided to advocate together.

The current conceptualisation of social wealth is something we have to discuss because of two significant trends that are shaping our societies: rapid digitalisation of life and non-linear climate change.

These trends are not similar, quite the opposite. While digitalisation provides new opportunities for value creation and conceptualisation of value from the intangible realm, non-linear climate change challenges the whole concept of growth. This is especially true after the recent scientific discussions regarding the impossibility of so called decoupling of growth which was something that was thought to be possible in the early days of digitalisation.

Nevertheless, Europeans are united to mitigate climate change. According to a recent study, 92% of Europeans support making EU climate neutral by 2050.

Despite such widespread support, it’s been a struggle for EU member states to reach their climate targets. This was revealed by the European Environment Agency announcement that the EU is with a high probability going to miss its 2030 climate targets.

This is the problem I think we should talk about today: why does it seem that this important transformation is stuck with small arguments between politicians and not much is enough is done in the private sector? I’ll propose later that the economic system is to blame, and that we need to “reset capitalism” as framed by the Financial Times to increase our societies transformation capabilities to a sufficient level.

In any case, the next ten years are going to be crucial for our societies and we know for certain that many things will be different in the year 2030. Because of this, we want to open up a debate about not only the means and metrics of the society, but also the aims and purposes of the economy.

This means asking very fundamental questions about the economy, such as “what we should prioritise?”, “what we should value?” and “what is worth doing with our time that is inherently limited?”

Because, to paraphrase Gramsci, “the old world is dying but the new one cannot be born yet”, we would need a new agenda that inspires action and creates an anchor for our current institutions to tie around their transformative capabilities and opportunities.

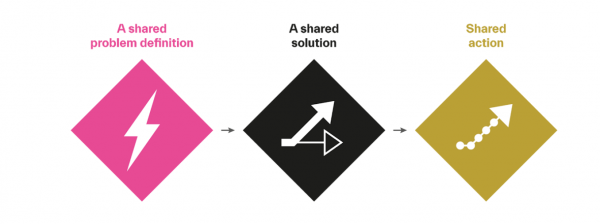

Which finally brings me to the topic of the publication. We propose that the EU member states are lacking transformative capabilities firstly because there is no shared definition on what is the problem: why it seems so difficult to get anything significant done. Demos Helsinki suggests in the publication that a good candicate for the shared problem would be a set of systemic problems which has a root cause in the current economic system and economic policy.

If this indeed is the problem we are phasing, then it makes sense to also try to identify a shared direction or solution to this problem. We suggest that Economy of Wellbeing could be such a solution. Finally, in the publication, we provide some initial stepping stones towards such Economies of Wellbeing.

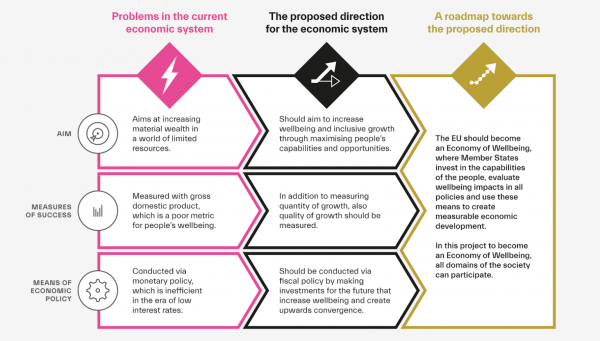

The problem we suggested is three-fold: there is a problem with the current means of the economic policy, in the metrics we use and in the aims that the economy thrives for.

Firstly, the current toolbox is more and more limited. Fiscal investments are uncoordinated and their size is capped. As long as the Member States do not agree on a shared fiscal policy direction or make coordinated investments, the pressure increases to use the only tool in the toolbox – monetary policy. But monetary policy is constantly less effective due to the secular stagnation and low interest rates. It simply is not very effective tool these days. Many respected figures, such as the previous ECB chief Mario Draghi, have articulated for coordinated fiscal policy in the EU.

The second problem is with the metrics and measuring of success in the economy and economic policy. The role of GDP has been challenged in various kinds of discussions for at least 40 years, but it has prevailed as a number one metric for the success of policies, and sometimes for a good reason. However, GDP is not meant to measure for example people’s wellbeing.

The third problem is the problem I started this keynote with, which is the fact that the economy aims for increasing material wealth in a limited world. Climate change is nothing but one of the side effects of this impossible tension.

If we agree that these three issues characterise the economy as it is today, we should of course consider a new direction for the economic system. Remembering the fact that I started with, that the size of the economic pie grows more when there are better investments, it might sound conflicting to propose that the goal of the economy should be to increase wellbeing and inclusiveness via maximising people’s capabilities and opportunities.

But this perspective becomes more lucid when we acknowledge that there is not only a quantitative element in growth, but also a qualitative element: growth has different qualities. Some growth is better than other growth. I want to emphasise that this is not about simply increasing people’s capabilities for the sake of more growth, although this is something that usually happens as a side effect of increasing capabilities; and that the meaning of “quality of growth” is not only about adding the cost of externalities to our measurement of economic growth. Instead, quality of growth means that there is not one but several “pies” we are trying to grow, and it has always been this way. But because of our limited conceptualisation of value that derives from our tendency to reduce all incommensurable values to value measured in currencies, it has seemed that there has been just this one pie.

Digital data can help to measure better various kinds of values that are produced via investments; political discussion can fruitfully argue about balancing those values; and fiscal investments can be used as means to guide investments to produce various kinds of values.

Regarding fiscal investments, I’ve been told that budget discussions in the EU can be slightly tricky at times… To support such discussions, a symbol or an anchor is needed. This concept should crystallise the goals, metrics and means of economy and build high level consensus on what constituets responsible and effective fiscal policy.

Demos Helsinki proposes that Economy of Wellbeing should be such an anchor. This means that member states would do investments in wellbeing and capabilities of people to create quality growth. Advocating such an inclusive economy that works for people is within the EU’s mandate.

It’s crucial to understand that measuring quality of growth is much easier than before because of digitalisation. It’s both much more easy than before to collect and analyse comparable data across domains and countries, and also create learning governments that measure the success of all policies based on their wellbeing gains.

Indeed, Demos Helsinki proposes that the EU should become an Economy of Wellbeing, where member states invest in the capabilities of the people, evaluate wellbeing impacts in all policies and use these means to create measurable economic development. Naturally, this is not a project only for governments, but instead it should be a sort of a battle cry for all organisations across the society to join forces and participate to build a better society together.

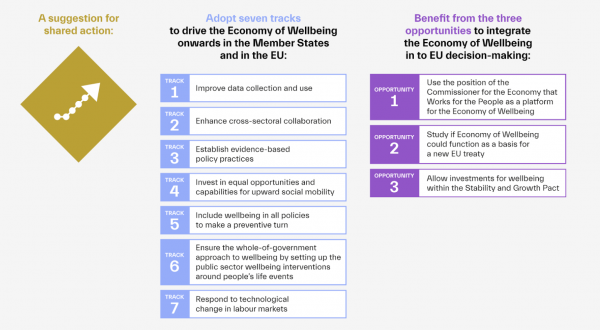

Based on the council conclusions on the Economy of Wellbeing, we propose seven tracks that demonstrate good directions to quickly accelerate Economy of Wellbeing in the EU and in member states. We also highlight three interesting and slightly provocative opportunities to integrate Economy of Wellbeing in the EU, and I’m going to end this blog post by describing their contents.

Firstly, we highlight the opportunity for the Commissioner of the Economy that Works for People to function as a platform for Economy of Wellbeing. In this sense, the “Economy that Works for People” could be a synonym for the “Economy of Wellbeing”.

Second, although absolutely no one wants to discuss a new EU treaty these days, the time will come when it’s going to be back in the table. We suggest that the potential for the Economy of Wellbeing to function as a basis of such treaty could be investigated well in advance.

Third, to encourage coordinated and larger fiscal investments, we propose that investments that clearly create direct wellbeing gains while at the same time creating economic prosperity could be excluded from the Stability and Growth Pact to encourage investments.