The business concept “platform” is widely misunderstood. Platforms are wrongly defined as digital tools that help two or more groups to interact. This causes much undesired ambivalence: Are electric scooter companies platforms? How is the interaction between the driver and the passenger in Uber different from a cab company? The…

The business concept “platform” is widely misunderstood. Platforms are wrongly defined as digital tools that help two or more groups to interact. This causes much undesired ambivalence: Are electric scooter companies platforms? How is the interaction between the driver and the passenger in Uber different from a cab company?

The ambivalence is undesired, because severe market failures emerge often not because markets work in the wrong way, but because market concepts are misunderstood. An example of this is the dot com bubble, where concepts of viral growth and network effects were confused. This led investors to massively overvalue some startups such as Pets.com. A similar development can happen when companies that are not platforms, such as E-scooter companies, are valued as platforms.

The good news is that a better definition of platforms provides tools for creating new business models and helps to avoid bad investment decisions.

This text explains why platforms are misunderstood and how they should be defined, how the new definition helps coming up with successful business models and why platforms indeed should be considered not only part of the economy but a next phase of the economy.

Platforms are more than just tools

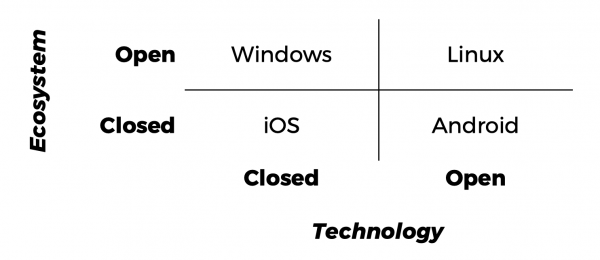

As many authors have concluded, the platform discussion is often misled by the simple fact that the word platform means two different things. Originally, a platform was the core of many products within a company (GM car chassis) or the level of competition within an industry (Intel processors). Intel processors are a technological platform that sets the service level that every computer manufacturing company needs to deliver. Microsoft Windows was a technological platform: it enabled many small software firms to create products on a level playing field. Uber as a technological platform creates the conditions of competition for Uber drivers.

A technological platform is a tool that defines the competition of an industry. Economic platform is a way to create value via network externalities, facilitating interactions of distinct groups and control of data instead of tangible resources.

The other meaning of the word platform has originally developed from the technological meaning. Consider Microsoft Windows: When more and more people bought the operating system, it made more and more sense for software companies to produce new applications for Windows. Furthermore, the more there were applications, the more useful the operating system was, so more people bought it. Windows, in other words, produced positive network externalities that are also called network effects. This is one feature of an economic platform. In this sense, economic platforms have common ancestors with technological platforms. Nevertheless, they are different beasts.

At times, it’s useful to discuss technological platforms. Understanding the technological platforms that a business uses to remain relevant is a common topic in companies. But when the technological meaning of platforms dominates the mind-sets of leaders, the important discussions regarding the disruptive potential of economic platforms might seem absurd.

Indeed, it’s the economic meaning of platforms that really challenges current ideas. While technological platforms are a sort of hygiene factor in companies, economic platforms are the source of insurmountable competitive advantage for some – and the cause of becoming irrelevant for others.

Due to this, the word “platform” from now on in this text refers to economic platforms.

A comprehensive definition of a platform

A platform has the following characteristics:

- It benefits from network externalities

- It facilitates the beneficial interaction of two or more user groups (I hereby use the term “platform markets” to refer to different user groups, because the word ‘user’ is often understood too narrowly)

- It owns value units

These “characteristics” are actually just good ideas for businesses. Brought together, however, they enable business models that are much more effective than the pipeline businesses of the industrial age.

Network effects

Positive network externalities or network effects happen when an interaction causes externalities that increases the utility of a future interaction. For example, a click on Amazon.com improves the search results and recommendations for all Amazon users. This improves the service, leading to more users and more sellers. Joining Uber Eats as a user increases the desire of a restaurant to deliver through that platform; joining to Uber Eats as a restaurant increases the likelihood that users find the food they desire on that platform.

These kinds of direct and indirect network effects are the defining characteristic of a platform because digital tools allow gaining from them in a significantly larger extent than what was previously possible. However, it would be a mistake to define platforms solely by network effects.

Facilitating the beneficial interaction of two or more platform markets

Facilitating the beneficial interaction of two or more platform markets means that participating in an interaction on platforms is beneficial to two or more groups of people. This business model feature provides two benefits. Firstly, it often enables an unfair competitive advantage against established businesses via Not Even Mine business models. Secondly, it provides protection from platform competition through the ability to hold platform markets.

A classic example of a Not Even Mine business model is the car rental business, vividly explained in the book Platform revolution. In short, a traditional car rental company operates according to Just In Time principles: a perfect accomplishment for them is to provide the car to the customer at the same moment that the customer walks out from the airport front door, without storing it in the garage longer than necessary. A platform company, nevertheless, can have a Not Even Mine approach: if people are willing to rent their own cars while they are travelling abroad, a platform company might have an excessive number of cars waiting at the airport. There is no extra cost for the platform company to keep the cars waiting empty as they are owned by other travellers. A Not Even Mine business model, when applicable, always trumps the Just In Time model, but it requires balancing of the several platform markets with various incentives to function.

The protection from competition by having a beneficial interaction is a crucial feature. If the business model lacks a beneficial interaction between two or more platform markets, the company is a pseudo-platform (see the respective chapter below). The protective mechanism is nontrivial, but an anecdotal example is helpful.

If one seeks to enter a food delivery market in a city where there already is a functional food delivery platform such as Meituan, GoJek, Woowa, Wolt or iFood, one needs to accomplish two actions simultaneously:

1. Convince all the users to switch to your platform

2. Convince enough restaurants to switch to your platform

It’s possible to do one of the two with advertisements, price wars and having a better product. Especially users are able to do multihoming, meaning that they are willing to use several apps simultaneously. But restaurants are more difficult. The most popular restaurants are already operating at full capacity. They would only switch if you can promise that there is at least same amount of profit to be made in the new platform. You would need to convince the restaurants that from day 1, there will be users; and users that from day 1, there will be all the restaurants they desire. On top of this, you need full delivery capacity from day 1.

You only have one shot to accomplish this, because if the users are disappointed the first time they use the app, they won’t return.

No matter how much resources you have, this is an impossible feat. No sane entrepreneur would try this. Established food delivery platforms are protected via their several markets.

Value units

For a traditional company, the information about what it has in stock and on the shelf is just one piece of business information among many other. For platforms, this information is the starting point of all business. The value unit is the information provided by the holiday apartment rental on AirBnB and the location information of the driver on Uber. This information is the raw material of platforms, and – crucially – it’s owned by the platform.

From a user perspective, the value unit is the information that the user needs to make a decision about using the platform. In other words, the value unit is not the provided good or service, but the information about the good or service.

So, the platform is defined by 1) benefitting from network externalities, 2) facilitating interaction between at least two distinct user groups and 3) the ability to own value units. What’s remarkable is that many current business models tick two of the three boxes in this definition. I call these companies proto-platforms, pseudo-platforms and hypo-platforms.

Proto-platforms

Microsoft Windows benefits from network externalities and facilitates the interaction of two platform markets (software users and programmers), but it doesn’t own value units. Because of this, I call it a proto-platform.

Although Windows was hugely successful, it was successful because it managed to get a position as a technological platform. If Windows would have owned their value units in a similar way Apple owns the offering in their App Store, Microsoft would have dominated the digital revolution even more than it did. In retrospect, we are all lucky that Bill Gates had enough of a hacker heart to keep his life work open in economic terms although any Linux affiliate would be quick to note that the technology was closed. It could have had much more market power.

Pseudo-platforms

E-scooter companies such as Lime, Tier and Voi, as well as all Chinese dockless bike-sharing companies, benefit from network externalities (more scooters mean better service for users; more users means the possibility to provide more scooters) and own the value units (location information of the scooters). But because they own their own products, they only have one platform market. Because of this, these e-scooter companies are not platforms according to the aforementioned platform definition.

As mentioned before, the beneficial interaction of two or more distinct groups is not merely a nice-to-have feature. Instead, it’s a crucial feature if one desires to create a platform business. The lack of multiple markets means that these companies cannot protect their business: all monopoly rents are by definition temporal. They are unprotected from competition. They are falling victim to the same mistake that killed the dot com companies. I call these kinds of companies pseudo-platforms.

The temporality of monopoly rents was true in almost all cases in pipeline businesses as well. Successful pipeline businesses had unique resources. But platforms are different. An investments to pseudo-platforms such as Lime with an expectation that its value is generated similarly to Uber is going to yield negative returns.

Hypo-platforms

A third group of not-quite-platforms is companies that facilitate the interaction of two or more user groups and own their value units but don’t benefit from network externalities. An example of such a company would be a mall or a bazaar owner. These companies are useful but not transformative in any way.

Platform business models

Understanding the pitfalls of hypo-platforms (inability to scale), pseudo-platforms (unprotected) and proto-platforms (unfulfilled potential) helps designing winning platform business models. But a better conceptual understanding of what is a business model is needed as well.

In designing platform business models, typical tools for business model designs are insufficient. For example, topological approaches such as the Business Model Canvas (Osterwalder) are not helpful, because they fail to take into account the dynamic nature of network effects and feedback loops. Instead, the business model design should start from the atom of the economy: transactions.

Platform transactions are different

Unfortunately, very few authors bother to define platform economy. But its meaning should be clarified here, as the word economy is a strange one. The economy is both a very large thing, incorporating all the companies, banks and other financial institutions, and a very small thing: something that happens between two people when they act in a manner that benefit both of them. While it’s usually the first definition that comes to mind when people talk about platform economy, it’s the latter that should be investigated further.

Previously, indeed, a transaction included two people. In a typical case, one got paid, and the other got a product or a service. Both of them, in other words, gained something. What was left unsaid was that many other people, who did not participate in this transaction, lost. A car purchase increased traffic and pollution, and these externalities were seldom paid for by the two participating in the transaction.

Transactions in the platform economy are different. While the aforementioned characteristics of the transaction still apply, there’s a new layer in place. This new layer is sometimes called the network, and sometimes the ecosystem.

When a platform transaction happens, it causes positive network externalities. Thus, many or all of those who partake in the same platform gain.

Previously, a Volkswagen buyer probably didn’t want other people to buy the same car. After a point, there was little benefit from this to the buyer. But a Tesla autopilot gets better when other people drive a Tesla. It makes sense for a Tesla driver to wish that more and more people buy Teslas.

The platform business model design starts from identifying possible transactions and their externalities, and identifying ways to create feedback loops from them. I present a method for doing this with Causal Loop Diagrams in my book Platform Economy and New Business Models (October 2019 in Finnish).

A slightly broader view on platform business models is also helpful. First, it’s important to understand that a business model is actually a combination of profit model (how do the intangibles and currencies circulate) and business system (who does what). Platforms transform both parts of the business model.

The profit model needs to include other values on top of the monetary value. This is because many platform markets are incentivized with values that are not measured in cash. Thus, the profit model becomes a sort of a benefit and pitfall analysis regarding all participating actors.

Business system is even more interesting. As mentioned in the book Platform revolution, the core functions of firms are inversed. This is because it’s much more difficult to facilitate network effects inside the company than it is to facilitate them outside the borders of the company. Due to this, marketing turns from a marketing department to Word-of-Mouth. IT moves to cloud. R&D changes from secret departments to listening to the user. Even the role of the strategy department changes – from horizontal and vertical growth to enabling market convergence. Designing a platform business model without taking this into account will lead to failure.

The next phase of economy

In this text, I first explained that the misunderstanding of platforms has already misdirected investments. I then pointed out that the word platform has two meanings: a technological meaning and an economic meaning. While the technological perspective is sometimes useful, the economic platforms are the true source of disruption. Building on the definition of the economic platform, I demonstrated how there are proto-, pseudo- and hypo-platforms and how learning from them can provide a good understanding of the requirements of a platform business model. Lastly, I described how designing platform business models starts from redefining transactions and how that changes both sides of a business model: profit models and business systems.

In the last segment, I started from the atom of the economy – the transaction. Then I described how business models in companies change to benefit from this shift. In the next text, I hope to broaden the view to describe how the whole of the economy changes, when businesses change in the aforementioned manner.

A writer, Johannes Koponen, is publishing a book Platform Economy and New Business Models (Alustatalous ja uudet liiketoimintamallit) in October 2019. At Demos Helsinki, he is responsible for keeping Demos Helsinki five years ahead in their thinking. Follow @johanneskoponen on Twitter.