Cities now account for 70% of the world’s CO2 emissions. From Oslo to Copenhagen to Växjö, cities both large and small have realised that where states have failed on an international level, cities can still succeed on a local one. Cities have shown the will to take the lead, and in…

Cities now account for 70% of the world’s CO2 emissions.

From Oslo to Copenhagen to Växjö, cities both large and small have realised that where states have failed on an international level, cities can still succeed on a local one. Cities have shown the will to take the lead, and in doing so, seem to have realised something vital: if cities are where emissions occur then they are also where emissions can be curbed.

Although the targets and measures of cities are local, they are a catalyst for a transformation that is global. Currently, over half of the world’s population lives in urban areas and by 2050 that number is expected to increase to encompass two thirds of the people living on earth.

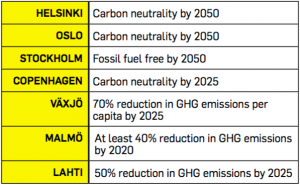

Whereas nation-states are constricted by the election period timeframe, cities are setting their targets to 2050 and beyond. Helsinki, Oslo, and Stockholm all plan to be carbon neutral by 2050. In the Nordics, even smaller cities are realising the importance of tackling climate change.

Some of the most exciting innovations include Stockholm’s central railway station plans “to harness the body warmth of 250,000 daily commuters to produce heating for a nearby office block. The body heat would warm up water that would in turn be pumped through pipes over to a new office block” and Oslo’s decision to ban cars from its city centre by 2019, the first European capital to do so.

Becoming a forerunner in environmental matters has and will continue to garner social and economic benefits for the cities that embrace it. Växjö’s shift to biomass, for instance, has enabled the city to become less vulnerable and less dependent on energy from the outside. Further, it has created jobs and stabilised energy prices, all the while being a more environmentally friendly alternative. Malmö, on the other hand, has placed its bet on the correlation between creating a liveable city and attracting new citizens and business. The city’s strategy envisions Malmö as “the sustainable city:” a clean, energy efficient urban area that harbours a cutting-edge environmental sciences research community, drawing in people and businesses alike.

Similarly, Copenhagen concedes that its ambitious climate plan requires investments, but emphasizes that they are still precisely that: investments. In the future, the project will bring about environmental benefits, but also well-being for denizens and a boost to the city’s economy. More bicycles mean more exercise, a cheaper utilities bill means more savings, and fresh innovations can become bestselling exports. At the same time, these investments form the backbone of new jobs.

With such promises, who wouldn’t want to join the ranks of these Nordic urban forerunners?

_________________________________________________________________________________

This is an edited chapter from Nordic Cities Beyond Digital Disruption, a report from the Demos Helsinki led project Smart Retro. The chapters are part of a series of blog posts featuring excerpts from the report and commentary interviews by world leading experts in urban development.

Praise for Nordic Cities Beyond Digital Disruption:

I truly believe Smart Retro is a promising and important project. We see so many interesting initiatives in cities today. But most of these are small scale and independent and never reach the broader mass.

– Anna Viggedal, Researcher, Ericsson.

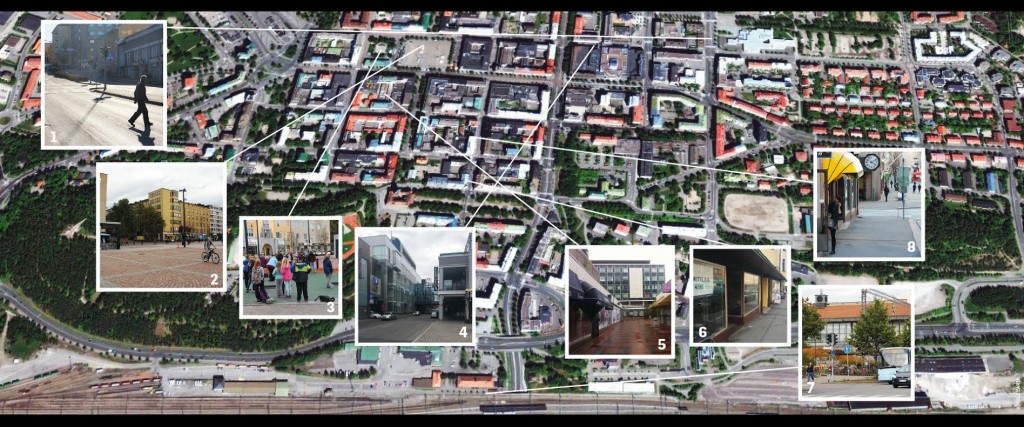

Picture of Copenhagen: here